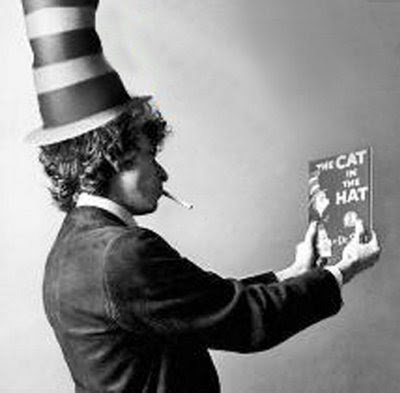

Hunter S. Thompson on Politics and Athletics

It's hard now in retrospect to appreciate how fresh and innovative Hunter S. Thompson appeared to be when he first burst on the journalistic scene in the 1970's. Because he was so influential and his style has been so copied that it is difficult to recall what the journalistic landscape was like before him.

Basically, professional journalism pre-Thompson was a pretty strait-jacketed affair. Most every article followed the so-called "pyramid style" which meant starting your piece with a lead sentence that summed up the entire story (President Kennedy was shot today in Dallas) in one line, then proceeding through a constantly broadening hierarchy of details (second most important fact, third most important fact, etc. etc.) and ending with the least important details (Jackie Kennedy wore a pink dress).

In those days, while every reporter had his name printed beneath the headline, nothing in the article would tell you anything personal about that reporter. If it did, then that was considered a flaw in the reporter's writing style. The truly professional reporter never revealed anything about themself in their articles. Not their opinions, their political affiliations or anything about their personal lives. A well-written piece of journalism was written by a reporter with only one goal in mind - the facts and nothing but the facts. The story was all that mattered, and the reporter himself (and it was almost always a he) was supposed to be invisible.

There were always those who were critical of that journalistic form. Critics claimed that such high standards of objectivity were mostly a myth. For example, the editor displays bias through which stories they assign reporters to cover and which ones they ignore, while the reporter shows bias simply by which facts they decide to mention and which facts to omit. To write an article pretending as though the reporter had no views of their own or were completely uninfluenced by what they observed, was considered by some critics to be fundamentally dishonest.

However none of those critics ever went as far as Hunter S. Thompson did in trashing the traditional form. Thompson's contribution to journalism was to show how to blow the standard journalistic model to smithereens and still inform the reader. In his twin classics Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, Thompson turned all the standard journalistic conventions on their head. He violated the ultimate taboo of traditional journalism by using the pronoun "I" in his stories. Instead of being a disinterested observer, Thompson declared all of his biases in up front while openly stating his personal opinion of all that he observed. Even more extreme, he sometimes admitted to being heavily intoxicated when he did his reporting. Of course journalists have always been a boozy bunch, but attending a presidential press conference on LSD?

Thompson was not the first to challenge the old conventions. For example Tom Wolfe (who once worked at the Springfield Newspapers, which wasted his talents by making him write obituaries) was experimenting with radically new reporting styles at least a decade before Thompson. Even as far back as the 50's Gay Talese and others were toying with new forms. But none of these writers were as talented, creative and goddam funny as Thompson. When he arrived on the scene his writings had a revolutionary effect previous pioneers had not. Suddenly every journalism student in America wanted to be like Hunter S. Thompson.

The results were not always positive. Sometimes an innovator unleashes a wave of copycats who do not have the same talent. Walt Whitman was so gifted that he brought respectability to free verse - but what followed in his wake was a deluge of really bad poems by those who used free form as an excuse to disguise bad writing. Some critics complained that Thompson's "New Journalism" as it came to be called, was too often an excuse for stoned escapades and sloppy reporting.

As for Thompsom himself, he never gave a damn about the controversy he created, and pretty much vanished from the scene for a long time. Some have said that success ruined Jack Kerouac by giving him the money to drink himself to death. Something of the same thing happened to Thompson. Always a man of enormous sensual appetites, money and fame turned him into a monster of over-indulgence. He got heavily into the porn world, where he had access to unlimited drugs and sex. Thompson stopped writing regularly, and the occasional short story or magazine article he wrote suggested his edge was gone. Some of the less kind critics complained that he had become a parody of himself, his once sparkling writing style reduced to spacy, bombastic rants.

So for a long time there wasn't much of anything literary coming out of Hunter Thompson, except for tales of ridiculous excess and rumors of his tragic decline. Then around the turn of the century, Thompson quietly resurfaced in an unlikely place - ESPN.com. At irregular intervals, Thompson began writing about sports. That was not entirely surprising, since early in his career Thompson had worked at several papers as a sports writer. Although best known for political writing, Thompson insisted to his ESPN readers that writing about sports was pretty much the same as writing about politics.

I have learned, in my life and work as a sportswriter, that big-time Sports and big-time Politics are not so far apart in America. They are both a means to the same end, which is victory. And why not? Victory is good for you and don't let anybody tell you different.

Hunter S. Thompson's book Hey Rube is a collection of his ESPN articles. Some of the pieces were outdated within a week after they were written about games most people didn't watch and no longer care about. But Thompson is absolutely great in flowing seamlessly between the world of sports and the world of politics, so even a minor basketball game can become an excuse to ruminate on great affairs of state.

As a political prognosticator Thompson was no better than he was at betting on sports teams, where he was crippled by a reluctance to bet against the teams he loved but knew couldn't win. Thompson wrongly predicted that Bill Clinton would run for mayor of New York and declared it impossible for George Bush to be re-elected in 2004. But when it came to analysing events after the fact, Thompson comes across as sharp as ever, as in this commentary on the 2000 presidential election.

The whole presidential election, in fact, was rigged and fixed from the start. It was a gigantic media event, scripted and staged for TV. It happens every four years, at an ever increasing cost, and 90 percent of the money always goes for TV commercials. Of course, nobody would give a damn except politics is beginning to smell like professional football, dank and nasty. And that's a problem that could haunt America a lot longer than four years, folks.

Let's face it: The true blood sport in this country is high-end politics. You can dabble in sports or the stock markets, but when you start lusting after the White House, the joke is over. These are the real gamblers, and there is nothing they won't do to win.

Nothing involving jockstraps or sports bras will ever come close to it for drama, violence, savagery, and overweening lust for the spoils of victory. The Presidency of the United States is the richest and most powerful prize in the history of the world. The difference between winning the Super Bowl and winning the White House is the difference between a Goldfish and a vault full of gold bars.

Much of Thompson's humor comes from his bitterly cynical take on the political process, which he constantly compares to the phoniness of professional sports. Like athletes, politicians are overpaid, fail to perform, are caught up in scandal and repeatedly betray their fans. The difference is that what happens on an athletic field, however contemptible it may be, has only a slight effect on your day to day existence. The Red Sox lost? Too bad, but the disappointment lasts only a few moment and doesn't effect your personal life. The same cannot be said of what goes on in the White House and in Congress. Yet, through all of Thompson's work there is an undercurrent of idealism, like here where Thompson pleads with his readers to go vote:

Anybody who thinks that "it doesn't matter who's president" has never been drafted and sent off to fight and die in a viscous, stupid war on the other side of the world - or been beaten and gassed by police for trespassing on public property - or been hounded by the IRS for purely political reasons - or locked up in the Cook County jail with a broken nose and no phone access and twelve perverts wanting to stomp your ass in the shower. That is when it matters who is President, or Governor or Police Chief. That is when you will wish you had voted.

That idealism, and the fact that he never lost it, even at the end when he finally committed suicide to escape aging into what he called "the no fun zone," is what made Thompson special. In Hey Rube, beneath the grand cynic sneering with unbridled contempt at both politician and athlete alike, is a true believer in American ideals. It is that idealism, rather than his experimental journalistic style, that made Hunter S. Thompson a great American writer.

J. Wesley Miller

Portrait of the attorney by Keith Sikes.

Wesley was a direct decendant of Miles Morgan, who has a statue erected to him in Court Square, as seen in another Sikes photo.

To read all about J. Wesley Miller click here.